Library of Congress Photos

| CLOSE WINDOW |

|

The following items are drawn from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print). |

|

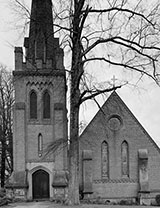

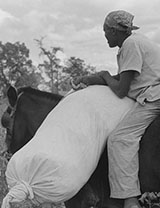

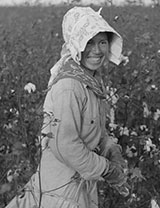

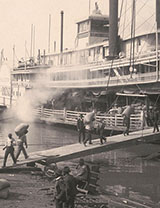

The 80 photographs of Mississippi here were drawn from the 175,000 images archived in the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress. All but eight are from the Division's Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph Collection. Five other images are from the Detroit Publishing Company collection; these were taken between 1880 and 1915. Three of the photos of Oxford, the origin of Faulkner's Jefferson, were taken by Jack E. Boucher in the 1970s; it's not clear how they ended up in the FSA archive. The other 72 were taken between 1935 and 1942 by the six FSA photographers who spent time in Mississippi: Arthur Rothstein, whose work centers on Lee, Pike and Lauderdale counties in August 1935; Ben Shahn, Natchez, October 1935; Walker Evans, Vicksburg, March 1936 (though he also shot images of Oxford and its environs, 3 of which are included here); Dorothea Lange, the Mississippi Delta, summers of 1936 and 1937; Russell Lee, Laurel, November 1938; and Marion Post Wolcott, the Delta, fall 1939 and summer 1940. The enlargements you can see by clicking identify the photographer, the place and the date of each photograph. The images produced for the Farm Security Administration include representations of life in towns and cities, but not surprisingly their emphasis is on rural life. The FSA photographers' specific assignment was to document the lives and practices and especially the hardships faced by farmers and farm workers during the Great Depression, and their pictures are typically framed by their own progressive political orientation. As a group the photographs evince much more empathy with the lives of their non-white and poor white subjects than is the case in most of Faulkner's fiction. This ideological focus is made explicit in some of the captions the photographers wrote for their images, such as this from Lange: "These cotton hoers work from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. for one dollar near Clarksdale, Mississippi" or this from Wolcott: "Interior of school on Mileston Plantation. School begins very late in the year and the attendance is poor until December because the children pick cotton." You can see the original titles and captions, when they exist, along with the enlarged images. It's important to view these photos through both the objective lens of the camera and the subjective point of view of the photographers. That is to say, the photos both represent the world of Yoknapatawpha County - and re-present it from a different perspective.                                                                                 As the "Out of Yoknapatawpha" location most frequently visited by Faulkner's fictions, Memphis, Tennessee, deserves its own place in our photograph album. The 16 photographs of Memphis below include 6 taken by Marion Post Wolcott in 1939. The first 10, however, though archived in the FSA Collection, were taken in the first decade of the 20th century by anonymous photographers working for the Detroit Publishing Company, famous at that time for their huge list of postcards featuring scenes from across the U.S. Ideologically or politically, the photographers who worked for the Detroit Publishing Company had a very different assignment from the men and women photographers of the FSA: to capture the country's best side.         ![General For[r]est Monument General For[r]est Monument](http://faulkner.iath.virginia.edu/media/resources/DISPLAYS/PHOTOdet 4a13369t.jpg)        Memphis appears in 34 of the 68 Yoknapatawpha fictions. The second most frequently used "Out of Yoknapatawpha" location is New Orleans, which appears in 16 texts. The four photographs below were taken from the Detroit Publishing Company Collection at the Library of Congress, and like the early photos of Memphis above, were shot during the first decade of the 20th century. Unfortunately, we don't have any photographs of the antebellum New Orleans that Charles Bon introduces Henry Sutpen to in Absalom, Absalom! - but of course that "New Orleans" is essentially the creation of Mr. Compson's imagination, which is a good reminder that none of the photographs in this gallery should be confused with the world that Faulkner's own imagination created in those 68 works of literature. His texts and the photographs are all re-presentations of "reality."     Citing this source: |