Railton SW Essay

| CLOSE WINDOW |

|

University of Virginia |

|

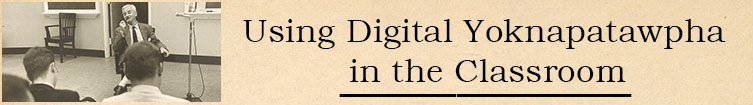

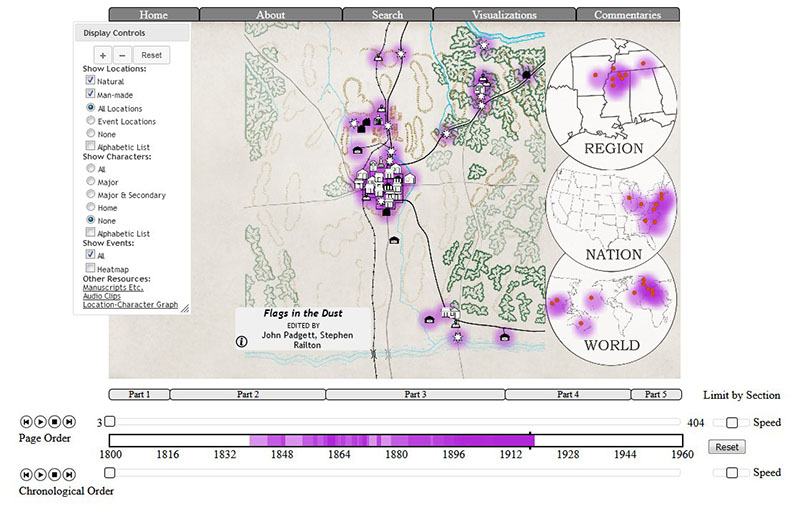

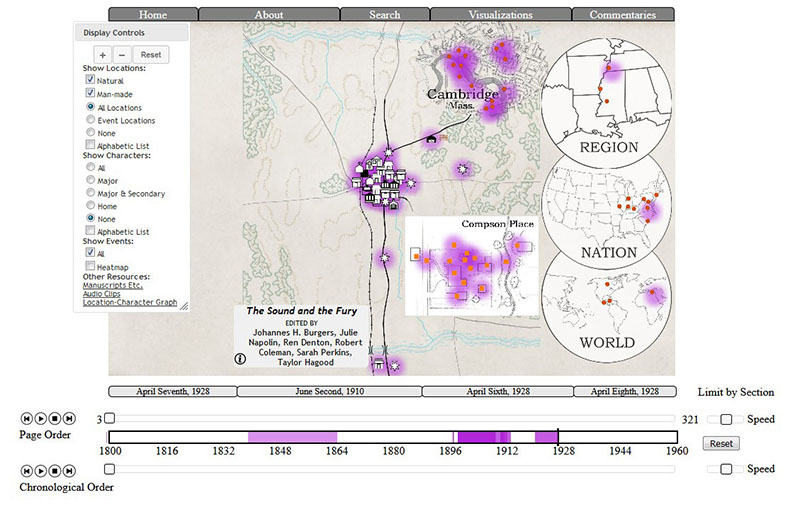

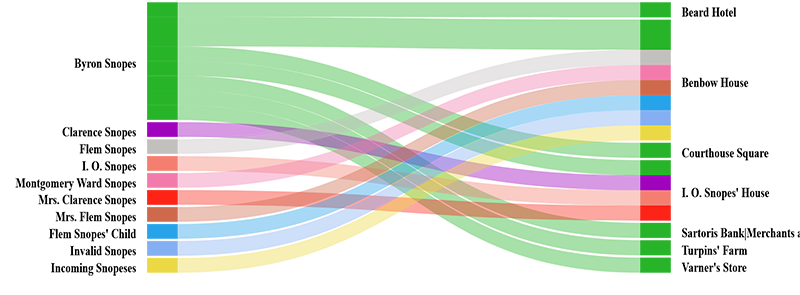

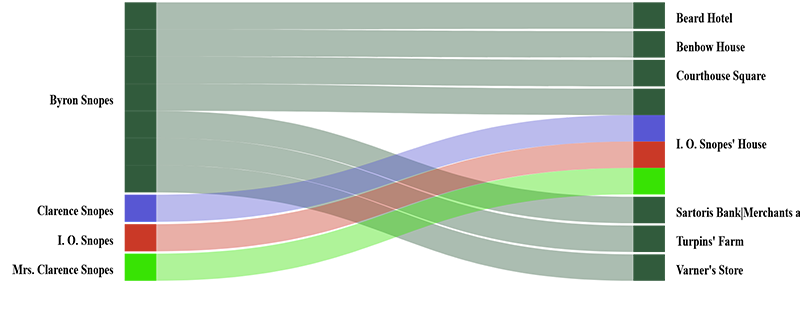

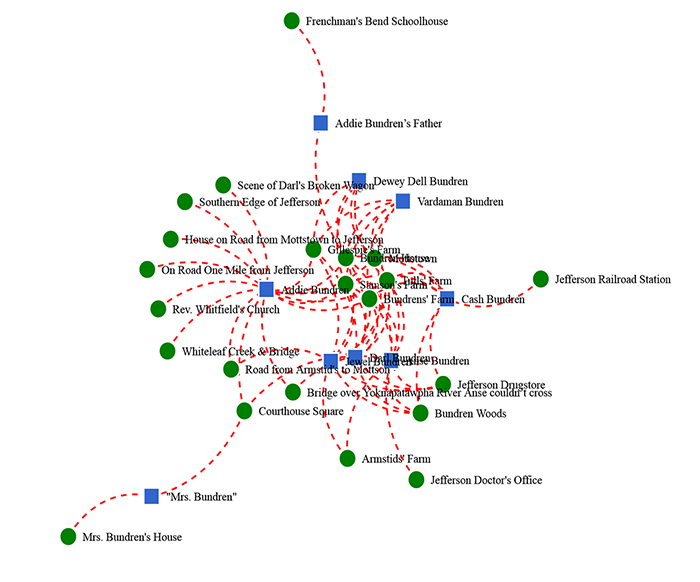

Assignment: I’ve never asked students to do this before – explore and report on how you used, or tried to use, Digital Yoknapatawpha to investigate something that interests you in Faulkner’s fiction. I don’t have a specific model in mind for what you can and should do. Instead, I’m hoping that you’ll teach me all the different ways there are to do both these things: use DY – and explain in writing how you used it and how well it worked as a resource. But I feel like I should at least provide some examples of the kinds of digital investigations you can undertake, and the ways in which you can report your results. So here, in schematic form, are 5 such examples. Each starts with a question about Faulkner’s work, applies an aspect or a functionality of DY to that question, and comes away with at least the beginning of an answer. I’ve tried to arrange them in order from the most basic to the most sophisticated, but any of these 5 would meet the goal of the assignment. 1. Faulkner’s interest in “the past” is well known, but can we be more specific about what kind or kinds of “past” he writes about? Can DY’s timelines for his first three Yoknapatawpha novels give us some way to begin answering that question? What I did: From DY’s book shelf (http://faulkner.iath.virginia.edu/) I selected each of the first 3 novels we read, which are also the first 3 Yoknapatawpha novels he published, and asked DY to “Show events: All” for each of them. This turns a lot of the map purple, of course, and it is interesting to think about the way Faulkner’s imagination re-centers each novel in space, in various parts of his mythical county. But I am investigating the way he locates each story in time, so I’m more interested in the purple on the timeline below the map. (NOTE: to make sure I could see it on one screen, I maximized screen size, using F11 key on my PC.) Below are the 3 maps and timelines – and remember that everything to the left of the vertical line on each timeline happens before the novel begins, i.e. is in “the past”:    For the assignment: I’d report on what I saw comparing these 3 re-presentations. I saw that in all 3 cases, a lot happened to the left of the vertical line – i.e. all three narratives go back often into the past. I was frankly surprised to see the amount of purple on the last of these 3; I was expecting the past to be less present in the narrative of As I Lay Dying. I could follow this up by using the Play by Chronological Order function, play NextEvent button, to go through the narrative one event at a time to see what kinds of things happen in this novel’s “past.” Instead, I followed out my desire to compare and contrast the 3 novels, and noticed the following: Flags in the Dust spends the most narrative time in the past (purple is deeper color) and goes back further, to the Civil War (1860s) and beyond, to the Old South before the war; it looks like there are one or two events in The Sound and the Fury from that historical period, but mostly the “past” in this novel occurs during the lifetime of the Compson children (1896 – present); As I Lay Dying has no events that occur before the 1880s, so its “past” does not include the Old South or Civil War at all. I’d conclude the assignment by spending a couple sentences talking about what these results might give me to think about, and maybe how I might follow them up. For example, the results seem to suggest that “the past” in Flags is Southern historical, but in the other two novels “the past” is something different – say, personal rather than social. To follow this up, I could compare earliest events narrated in each novel… [How I made the illustrations: if you want to illustrate your assignment, there are a couple ways to do it. I made these 3 images by opening PhotoShop, using the PrintScrn option (Fn+F11) to capture each webpage, then cropping the images and saving them so I could insert them in Word. See next example for another way to save images.] 2. In class we noted that originally Faulkner’s first Yoknapatawpha novel was going to be about the Snopeses, especially Flem, but then he put that manuscript aside to write about the Sartorises (and Benbows) instead. That made me curious about how the Snopeses figure in the novel he did write, Flags in the Dust. He relocated the focus of his narrative on the upper class families in Yoknapatawpha, but where do the “poor white” Snopeses show up? What can DY help me discover about that?  It might take a while to figure out what you’re looking at: in lefthand column (Characters), each of the novel’s Snopeses; in righthand (Locations) column, the specific places where he/she appears or is mentioned. The various colors of the lines connecting them allow you to see, for instance, that “Mrs. Flem Snopes” is linked to the “Benbow House.” At first I was surprised to see how many of the novel’s 10 Snopeses apparently appear at “Benbow House,” which suggested that those two white castes – the highest and the lowest – had a common meeting point, but when I remembered that the Benbows talk about the Snopeses, I realized the connections I was seeing didn’t necessarily mean physical or in-person connections. So I cleared the form and went back to the search options and re-selected for Name:Snopes (by using Name field instead of Family, I could further refine search), and then chose Character:Present (to eliminate instances when, for example, the Snopeses are only mentioned in text), and hit search again. Here’s what I got this time:  All but 4 of the 10 Snopeses who are Present or Mentioned in the novel have disappeared, meaning the other 6 don’t appear anywhere directly in the book. Further, this graph makes it clear how Faulkner’s imagination physically segregates the Snopeses who do appear. Three of those four members of the family appear only at a “Snopes” house (it’s the boarding house Bryon moves to). Byron is the novel’s one Snopes who occupies more than one place, but only two of the places he goes could be identified specifically with the upper class world: the Sartoris Bank, where he works, and the Benbow House. Looking at this made me realize that in fact his presence at both these places is ultimately criminal – he ends up robbing the bank at night, and he visits the Benbow house only in the dark, as a peeping Tom and then as a house-breaker and thief. PS: if I cleared the Bi-partite search and asked it simply to display the whole novel, I could show you all the places in Yocona County (as Faulkner is calling it in this first novel) where Faulkner never lets Snopeses imaginatively appear: 68 out of 75 locations altogether. The Benbows appear at 1/3 of the story’s locations, the Sartorises at almost 2/3’s of them. For the assignment: After stating my question and describing what I did using the Bi-partite graphing function, I spent a few sentences developing the implications of my discoveries, along the lines I’ve already suggested. If in the late 1920s Faulkner began writing about his home turf, and if his first imaginative impulse was to describe how it was being taken over and despoiled by Snopeses, he soon decided instead to create an imaginative version of home in which he could severely control where the Snopeses could go. [How I made the illustrations: in this case DY gave me a way to save the images – the Export button on the search form. I saved the .png files that DY exported and cropped them in Photoshop, but you don’t have to use Photoshop. As long as you name and save images Export-ed with DY’s visualization tools, Word will know how to make it fit your paper…] 3. Faulkner said at UVA on 15 February 1957 that he wrote The Sound and the Fury “to try to draw the picture of Caddy.” But how does her character appear in the text? Why do I have this feeling that she disappears from the novel as well as from the Compson home? What I did: using the Character Search engine (http://faulkner.iath.virginia.edu/characters.html), I selected Text: The Sound and the Fury, Name: Caddy, Either (Present or Mentioned), and hit Search. That returned both “Caddy Compson” and “Caddy’s Sexual Partners.” I clicked on her “Partners,” and saw that they appear in 4 Events, so I decided I that didn’t need to worry about them as part of the data. Back on the search page, where Caddy and her partners appear, I clicked on MapIt. This took me to a new map of the novel, curated to display only the locations and events in which Caddy is present or mentioned. I played through these one at a time using the PageOrder|NextEvent button and kept a rough count of pages which show up – page 4, 5, 7, 12, etc. According to that tally, Caddy appears or is mentioned on about 40 different pages in Benjy’s section, and on over 50 different pages in Quentin’s (often with multiple scenes on a page in both, for instance 4 times on page 124). But then she appears only 16 times in Jason’s section, and only once in the final section. So DY has confirmed my feeling that while she is a fairly constant presence in Benjy’s and Quentin’s minds and memories, she is barely visible, textually, in novel’s second half. Which brought me back to my original question with a specific focus for it. Assuming the novel is “the picture of Caddy,” what is the meaning of her absence? I.e., what role does she play in Jason’s life on April Sixth 1928? and what is her relationship to the events of Easter Sunday in the last section? Or, conversely, how do those two sections help to “draw her picture”? For the assignment: I’d describe my question, and then explain in detail how I deployed DY to explore it, and then I’d spend at least a couple sentences seeing where the novel, DY and I ended up. It is completely okay to say “I couldn’t make any use of what DY showed me,” as long as you show how you made a good faith effort to use it. It is also okay to say “well, I was disappointed that DY didn’t answer my question for me!” But I’m hoping that most of you will be able to say: “Although DY didn’t answer my question for me, it gave me a good vantage point from which to go back into the text and find an answer for myself.” In this case, I’d say: seeing how Caddy disappears from the fourth section made me focus on what “Caddy” and the two main events of that section (Dilsey in church on Easter, Jason chasing money) have in common, how what does happen in section 4 is also Faulkner’s way of creating the picture of Caddy – or at least of what Caddy “signifies,” to use a term that is also both there and not-there in the novel. 4. This time I started with the fact that, as I’ll mention in class, Faulkner tentatively used the same phrase – “The Dark House” – as the title of two different novels (Light in August, Absalom!). Dark houses are a regular staple of Gothic fiction, beginning with all the grim castles in British novels like The Castle of Otranto. Yoknapatawpha doesn’t have any castles, but the American equivalent is the mansion – or as it was known when it was found on a slave plantation, the big house. So I asked myself: where are the mansions in Faulkner’s fictions? and how are they described? What I did: I went to Locations Search (http://faulkner.iath.virginia.edu/locations.html) To narrow my search still further, I decided to click on each link and read the description of each of these locations. First click was confusing. Instead of a description, I read “See description for Compson Place: House on inset map”; this meant I had to do a second Search for Compson Place House, but when I did I was rewarded with a description that made the house sound (implicitly) very “Gothic,” and (explicitly) dark. Going through the other mansions on the list of links gave me a good idea of which ones fit this pattern – decaying or rotting, dark, etc. But that also made me realize that many of the old mansions were still well-maintained, so the big houses across Yoknapatawpha can’t be summed up with one set of adjectives. If I wanted to go further, with all of them or, for example, just with the ones that were described as “dark” or “decaying,” like the Compson place and Emily’s big house, the list of links to every event in each text that occurs at that location showed me how to use DY to give me a map of textual places I can go to keep probing the darkness of those houses. For the assignment: after explaining my question (how dark are the big houses in Yoknapatawpha?), I’d describe what I did using Location Search, what I saw (that while many of the big houses are rotting or decaying, many are still prosperous), and where that left me – realizing I needed to go back to the texts and look closely at what they actually say or imply about big houses, by re-reading the passages that are about those houses, or recount events that occur in them. Of course (as I could add) DY shows me exactly what passages I should look at. And it occurs to me that there may be a way to correlate the condition of a novel’s “big house” – whether it’s old and haunted or well-maintained – with the way that novel represents Southern society. So DY has given me a potentially valuable interpretive clue to pursue. By the way, you could do something similar with the residences at the opposite end of the county’s racial and economic order, i.e. with Locations>Type:Cabin. 5. This is a more complex way to explore the issue that example #3 above also identifies: the role of absence in many of Faulkner’s texts, how what or who is not there becomes a major element of the narrative, a powerful way to re-present the archetypal modern theme of loss – for instance, the dead god of Eliot’s Waste-Land or Jake Barnes’ manhood in Hemingway’s Sun Also Rises. In the Faulkner we read, absence becomes a portentous presence in many ways, but here I want to explore the hole that Addie’s death opens up in the world of As I Lay Dying. So my question could be phrased this way: “Addie Bundren is dead” – that’s the way Darl’s 5th section ends on page 52, with over 200 pages remaining in the novel; how is Addie gone and present, there and not-there throughout the whole story? What I did: This time I used the Visualizations>Location-Character Graphs>Force Directed. This kind of graph uses an algorithm to arrange all the Characters (blue squares) and Locations (green circles) in a text using forces of attraction and repulsion – similar to the way magnets can attract and repel each other depending on the orientation of their poles. In DY, the forces are defined by the number of times a Character or Location appears in an Event, the number of pages in each Event, and so on. The resulting visual display is abstract, but the closer the Characters and Locations are to the center and to each other, the likelier it is that they play an important role in the story – and conversely, the further apart and more peripheral a square or circle is, the less important it is likely to be. Because I wanted to see what this kind of re-presentation could reveal about Addie’s place in both the story and in the minds of her family, I started with Text=As I Lay Dying, Name=Bundren, Either Present or Mentioned. Here’s what I got when I clicked Search:

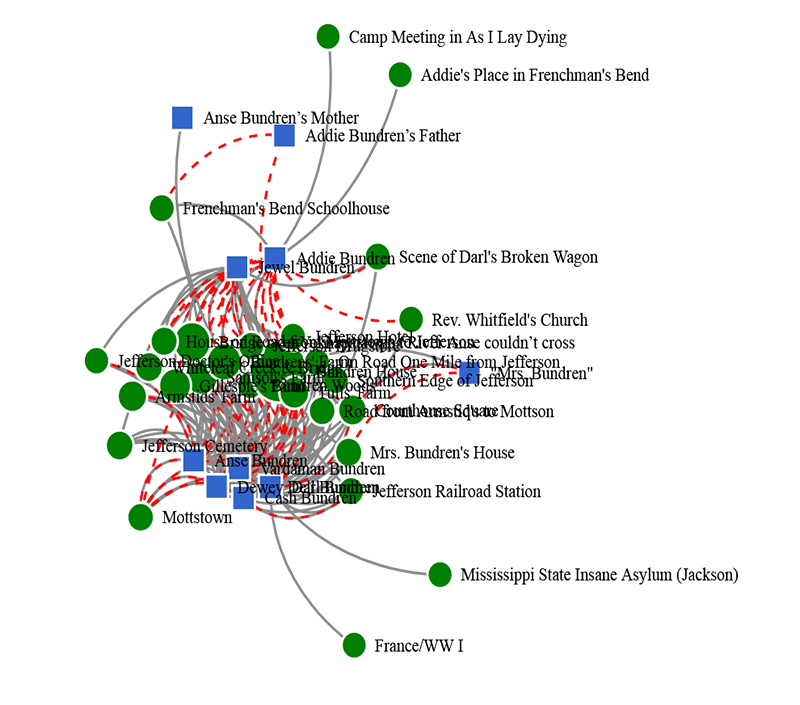

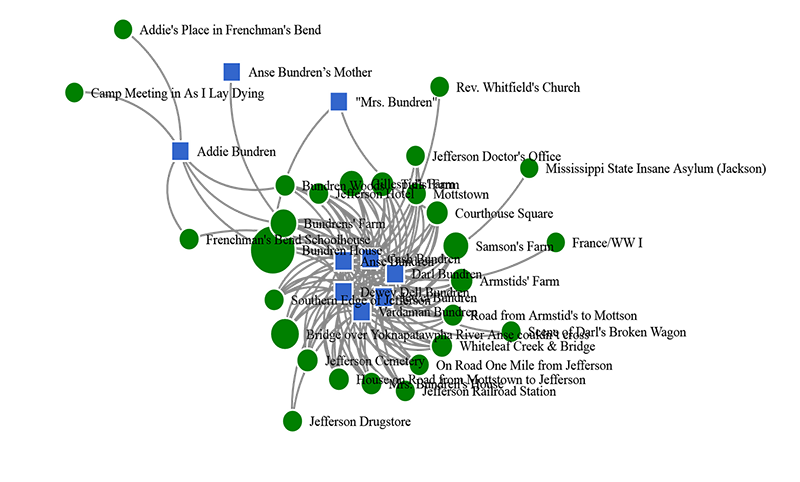

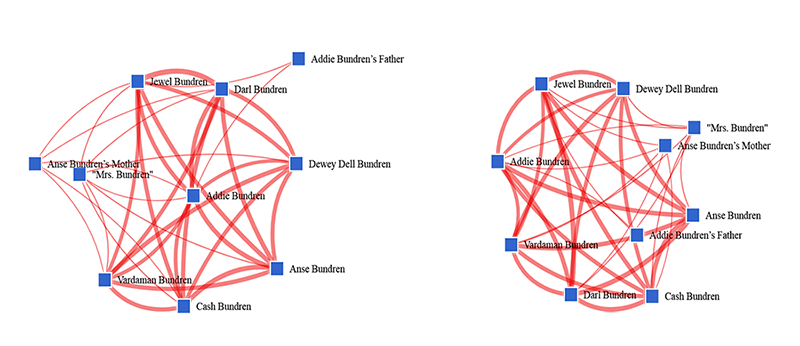

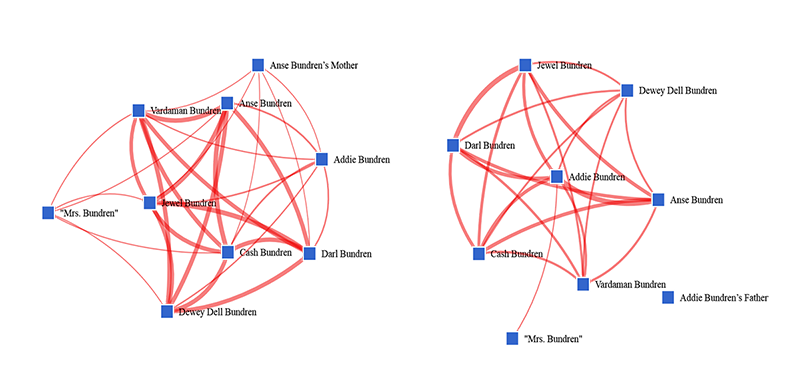

The large number of circles (locations), and the way so many of them are displayed together at the center, make sense, given that the novel tells the story of a journey. In addition, the graph above also brings Addie close to Jewel (her illegitimate child) and separates the two of them from the rest of the family, which may be significant and worth exploring further. But from this graph I can’t answer my question about how Addie is present even when she’s gone. So I refined my search, sticking with same Text and same Name, but changing status from Either to Present (which excludes events in which someone is mentioned in absentia). Here’s what I got:  NOTE: the fact that all the lines linking squares and circles are solid grey reflects the physical (Present) connection between characters and locations. Now this seemed to give me something to think about. All Addie’s family is inside the circle of locations, at the center of the graph. But she (and many of the locations associated with her life) have become peripheral. Next I revised my search terms, asking to see the pattern when Name=Bundren was Mentioned in the narrative but not physically Present. I knew that on this graph, all the linking lines would be red and dotted, but I didn’t know what else I’d see:  Now it’s Addie who is in the midst of the locations. She moves from the periphery on the Present graph to the center of the Mentioned graph. I confess I was happy to see this visual confirmation of my thought: that Faulkner knows how to put what has been lost, what isn’t there, at the center of a story. It’s a kind of Modernist paradox: the hole left by a crucial absence creates the gravitational force around which a narrative can revolve. And for the assignment I’d go through all this, what I did and what I think it reveals. And that’s enough for the purposes of the assignment, but in this demonstration I want to make one further point – about the fallibility of the kinds of data searching and displaying DY can perform. It’s important not to rely uncritically on algorithms. I’ll show you what I mean by using another visualization tool, DY’s Character-Character force directed graph, to look at same question: Addie’s place (present and/or mentioned) among the rest of the Bundrens.  Above, side by side, two different versions of what I got searching Name=Bundren, Either. In the one at left, the first one I got, Addie is again at the center of the relationships among the members of the family (and note, thinner the line between “nodes” [characters] the less frequent the narrative connection). But at right, what I got the second time I searched using the same search terms. As you can see, this time the configuration is quite a bit different, suggesting a different interpretation. I searched Name=Bundren, Either, eight more times. In the 10 different results I saw, Addie was at center 3 times, no one else more than twice, but no one version of this graph is definitively The Way that the data says the narrative establishes the pattern of interBundren relationships. (Mining big data frequently produces these kinds of variations; humanists can feel confident that there is no substitute for un-artificial human intelligence as the best way to interpret what A.I. is able to tell us – at least, no substitute as yet!) On the other hand, selecting Bundren, Present (below left) consistently puts Addie outside the central grouping (as we would expect, given fact that she dies 1/3 of the way into narrative). Bundren, Mentioned, however, regularly puts her back in center (below right).  In conclusion: I know how complicated all this can look, especially at first. There are so many variable, like “Status” field in Locations searching, or “Present vs Mentioned” in Character searching, or the icons and colors on the maps and timelines, and so on. Faulkner’s texts are complicated enough to start with – is it worth struggling to find a way to use a digital program to explore them? I can say: I hope so. But I have to admit that I see DY as an experiment, a way to see what Faulkner’s art and digital humanities can reveal about each other, and the results of the experiment are not yet in. What you’ll do with this assignment will be an important part of the experiment.

I’m hoping that once you take the plunge and start clicking around in DY, it will become clear what kinds of analytical opportunities it puts in your hands – or at your fingertips. (If not, let me know where you get confused – that’s part of the experiment too.) And that you’ll discover your own way to apply something in DY to something in Faulkner that interests you, and end up finding a good place from which to launch an interpretive inquiry into the world he created. What I am asking you to do in this assignment is to make a good faith effort to test how well DY can serve your curiosity, your desire to survey the thematic and aesthetic landscape of Yoknapatawpha. Good hunting! – to use a particularly Faulknerian trope. Citing this source: |