Manuscripts Etc.

| CLOSE WINDOW |

|

The following items are drawn from the William Faulkner Foundation Collection at the University of Virginia's Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library (http://small.library.virginia.edu/). |

|

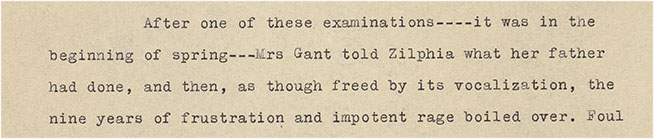

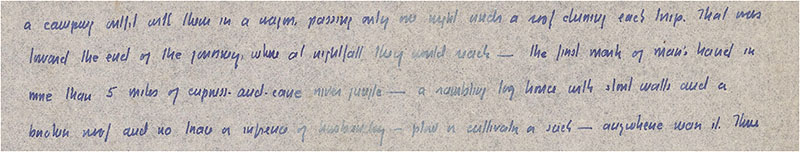

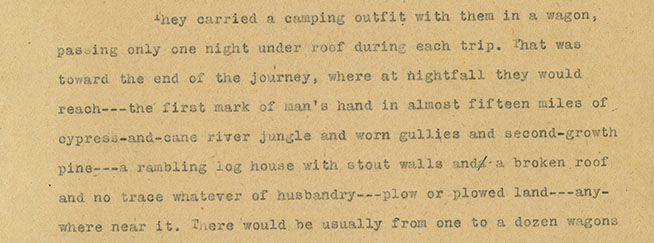

The Faulkner Foundation Collection contains three different versions of "Miss Zilphia Gant": a 9-page manuscript, an 18-page ribbon typescript, and a 23-page carbon typescript. That's the order in which the versions are listed in the collection's finding aid, but chronologically the first of these three is the ribbon typescript. It's undated, but probably dates from 1928, and is probably one of the two versions of the story that Faulkner submitted in that year to Scribner's Magazine. Some time later Faulkner decided to revise the story; the manuscript reflects a stage in that process, and the other typescript, which closely follows the manuscript, is the carbon copy that he would have kept when he sent the typed new version of the story out in 1930. March 1930 is when the story was bought by The Southwest Review. Although the story didn't appear in print for another two years, as a separate volume published by the Book Club of Texas, the published text closely follows that later typescript. Below is the entire 18-page typescript. Although the basic story it tells in its three sections is the same as the one published in five sections in 1932, there are a number of significant differences. The shorter typescript is chronologically more coherent: there is no inexplicable thirteen year gap between Zilphia hearing that her former husband's pregnant wife has gone to the "maternity hospital" and then hearing about her death in childbirth (page 17 below). All the offstage deaths in the story - the new wife's in labor, the murder of Zilphia's father and his lover, and accidental killing of her husband - are left implicit; the husband's death, for example, is referred to obliquely as "a motor fatality" (page 17). One of the most pervasive elements in the published text, the use of neighbors in both the "settlement" where Zilphia is born and in Jefferson to serve as the tale's chorus, providing commentary on its characters and events, is entirely absent from the typescript. Mrs. Gant's character, while still vivid, gets much less of the narrative's attention. Probably the most interesting difference, however, is the way the earlier version focuses more explicitly, even clinically, on Zilphia's sexual desires and frustrations. The scene in which Mrs. Gant catches her daughter lying on the ground with an unnamed boy is much longer. It begins when Zilphia sees the unnamed boy for the first time swimming "naked" in a pool: covertly she spies on him, "shaking slowly" as she "watch[es] him dress" (page 7). The scene continues when she reveals herself to the boy, who asks her "Did you ever play grown-up?" (8). That's what they are doing when Mrs. Gant suddenly appears; her arrival is the one part of this episode that Faulkner did not cut in revision. In the earlier version the racial element in Zilphia's desires is also made more explicit, more physical. Where the manuscript and the published story both say "she had been dreaming about negro men" (although at different points in the narrative; see page 9 of the manuscript below), the typescript says "she began to dream of negro men and she would wake and lie in the dark while her body jerked and shook to a dying rhythm, foul with its virginity" (page 18).                    Below are the first and last pages of the manuscript version. We can tell this version comes after the typescript above because it incorporates the revisions that Faulkner made in the typescript, for example the introduction of the "hulking" boy into the story's second sentence (compare page 1 above with page 1 below). The manuscript shows Faulkner actively revising: the passages he crosses out at the bottom of page 1 were rewritten at the top of page 2; page 9 shows his struggle to find the right ending. One thing to note in the manuscript's ending is how the "something" that "did happen" to Zilphia comes after she brings home the young girl; in the published story this happens before that. No version makes that "something" explicit. Its proximity to Zilphia's dreams about "negro men" (a feature of both the manuscript and the published text) is provocative, but most likely the "something" is menopause, which would explain the substitution of food for sex in her dreams.   Below are three pages from the 23-page typescript of the manuscript above. Faulkner used any kind of paper that was available for the carbon copies he made when he typed his work for submission; in this case he may have run out of manilla paper after page 4 - at least, pages 5-23 of the typescript are on very thin onion skin, and consequently very hard to read. Comparing page 1 below left with the first page of the manuscript above and the opening of the published text shows how likely it is that this typescript was the final stage in the story's composition.    One of the most conspicuous and puzzling elements in the text that the Book Club of Texas published is its unconventional use of ellipses, which first appears in the story's fourth sentence: "That was toward the end of the journey, where at nightfall they would reach . . . the first mark of man's hand in fifteen miles." Here those three dots seem to indicate something has been left out; elsewhere in the text, for example later in the same sentence, they seem to be used instead of dashes: "no trace whatever of husbandry . . . plow or plowed land . . . anywhere near it." None of the versions in the Faulkner Foundation Collection really explain what Faulkner had in mind by this unconventional punctuation. Below first: the typescript's version of another instance of this in the published text, where we find "After one of these examinations . . . it was in the spring . . . she told Zilphia." Second: the manuscript's version of that fourth sentence; its use of dashes is just as non-standard as the text's use of dots. Third: the way Faulkner turned the manuscript's dashes into an unusual 3-hypen mark when he prepared the new typescript. Pages 12 and 13 of the final typescript (above, center and right) show when Faulkner himself chose to use dots, and how unconventionally he deployed them; on page 13 you can see both dots and dashes in close proximity. It seems probable that it was an editor at the Book Club who decided to represent Faulkner's 3-hyphen marks with 3 dots instead - perhaps he got the idea from Faulkner's 9-, 11- and 12-dot sequences - but nonetheless it seems clear enough that the desire to experiment with punctuation in these passages was originally Faulkner's. What readers will still have to decide: why he wanted to do that at these points in this story.    Citing this source: |