Text Maps About Demo Legend

|

[The most efficient way to learn how to read and use our maps of Faulkner's fictions is to view the 11-minute "Demo" available on each map page. The point of this essay is to explain the interpretive policies and editorial practices that we used to create the maps.] |

About These Text Maps

|

The Digital Yoknapatawpha project begins with the conviction that the world Faulkner created in the last century still has a lot to teach us about the powers of the human imagination and the struggles of American culture. On the other hand, our goal is to re-present that world as much as possible in its own terms rather than ours - a distinction that requires explaining right at the outset. Faulkner's ideas about race, to take a particularly problematic example, while widely shared in his time, are essentially alien to the preconceptions of our own era. If the non-white inhabitants of Yoknapatawpha were real, we would probably refer to them as African American and Indigenous people. But they are characters, not people, and so our default labels for them are Negroes and Indians, terms that keep our Character database closer to Faulkner's texts. Similarly, the icons we use to display characters might look stereotypical, and even offensive -     But when you see them on the maps, remember that they do not represent a person, but a character born from Faulkner's imagination. He - or at least the culture he depicts in the fictions - did sort humanity into these four colors: when Brother Fortinbride preaches a eulogy for Rosa Millard, he pictures her in heaven, "where there are men women and children, black white yellow or red, waiting for her to tend" (The Unvanquished, 158). (And yes, Yoknapatawpha has one Asian American inhabitant, the unnamed "Chinese laundryman" mentioned in The Town, 321). Of course, "black" and "white" were the arbitrary and absolute categories that mattered most in Faulkner's world. While Jim Crow laws didn't keep people from having sex across the color line, the children of these interracial couplings were labeled with a set of terms - mulatto, quadroon, octoroon - that preserved the line itself. Even an octoroon (someone with 7 white and 1 black great-grandparents) was legally "black" in Faulkner's South. In his art Faulkner often challenges this racist practice - think Bon in Absalom, Absalom! for example - but even as he does so he perpetuates its categories; Bon's wife in Absalom! is inevitably referred to, in the novel and even by most Faulkner scholars, as his "octoroon mistress." The icons we constructed to represent the mixed race characters in the fictions -     - at least make the mixed race characters easy to spot on the maps and at the same time call attention to the unreality or socially constructed nature of fitting the rich range of his characters into this kind of grid. "Race" is one of the 64 fields in our Location, Character and Event databases. Users of DY will ultimately decide the value of separating Faulkner's fictions into these parts in order to re-assemble and display them in our interactive maps and other visualization programs. Right now my task is to discuss the other fields that don't necessarily explain themselves. LocationsWe have tried to display on our maps all the places that the fictions either use as settings or refer to. By our count, that's about 990 total locations in and out of Yoknapatawpha, many of which are used in multiple texts. The Location icons sort these places into 11 categories -            - a small enough set in our judgment to keep the map display from being too visually complex to be legible. However, using the Locations SEARCH engine you can also filter Locations via 146 more granular Types, by means of which, for example, the set represented with the "Public Building" icon is subdivided into "School" or "Jail" and so on. For a broader discussion of our maps of Yoknapatawpha, and their relationship to the two maps of the county that Faulkner himself created, see both the "Faulkner & Maps" exhibit in DY's Commentaries section and the "Mapping the Story" explanations that you'll find in many of our Notes on the Texts. The first point to establish here is that each of the project's 68 maps, along with all the data that is associated with it, is specific to a particular text; this means that those 990 locations appear in 2419 text-based Location entries, which can and often do vary. Take the Status field for the "Sartoris Plantation," a Location which Faulkner uses in 15 fictions. Although Flags in the Dust mentions that John Sartoris "rebuilt" the plantation's 'big house' after the Yankees burned it down during the Civil War (8), the rebuilt Sartoris mansion is there from the beginning to the end of Flags - so in the data for that text its Status is "Continuous." It is "Destroyed" in "Retreat," the short story that ends with the Union soldiers setting it on fire. It is "Destroyed and Rebuilt" in The Unvanquished, which includes the scene of its burning but also the new house that rises again from those ashes. (The maps allow you to get from a Location - the "Sartoris Plantation" in Flags, say - to a Cumulative Location entry, where you can see the other 14 times Faulkner re-uses and often revises this setting in the different texts.) Since "Yoknapatawpha" is a place that has no physical existence, deciding the location of each Location is always an interpretive act. The Authority field identifies the basis on which our decision was made in each case. The "Sartoris Plantation" actually appears on both of Faulkner's maps, right where the text of Flags says it is, "four miles away" from Jefferson (76) - so in this case our Authority for its position is "Faulkner map." But in some cases a Location moves from the place Faulkner assigns it on his maps. Take for example the "Armstids' Farm." On Faulkner's 1936 map it lies northeast of Frenchman's Bend on the road that Lena Grove is walking on when Light in August begins, and "Faulkner map" is our Authority for its position on the map of that novel. But when the farm appears in the earlier As I Lay Dying, it is clearly south of the Bend, adjacent to the river that the Bundrens cross on their journey to town; there the Authority is "Context (text, as interpreted)." In at least several hundred cases we have no clear evidence, either within a text or on a map, on which to decide where to put a Location; in those cases we acknowledge that we are making an educated guess by identifying our Authority as "Speculation." If you want to see exactly how often this happens, use the Locations SEARCH engine and filter for Authority=Speculation. And it's important to say that even when a map or a text provides good or at least some evidence, mapping the places used as settings or simply referred to in the texts is an inexact process. There is no GPS system that works in Yoknapatawpha. CharactersFrom the beginning one of the project's goals was to take advantage of the storage and organizational capacities of electronic technology to identify every single character or group, named or unnamed, present or only mentioned, that appears in the fictions. Of course we can't claim to have done that, but so far our Character database contains over 3700 separate characters or groups, and almost 5000 Character entries. That difference of 1300, of course, is because many of those 3700 characters recur in multiple texts, and as with Locations, each time someone appears in a text, we create a entry based on that appearance; these are then aggregated in the Cumulative Character Index. Though we gratefully acknowledge how helpful the previous scholarship about Faulkner's characters has been (see the project's Bibliography), 3700 is a much larger number than any previous index or guide contains. Those focus almost entirely on named characters, and so misrepresent Faulkner's world in significant ways. Most of them include, for example, the peripheral Baron von Rickthofen - the German aviator who taught the pilot who shot down Johnny Sartoris in Flags in the Dust - but not the Unnamed Ford Driver who caused the accident in which Old Bayard dies nor the Unnamed Blind Negro Musician who begs outside Rogers' restaurant, though if Von Rickthofen evokes the aristocratic past that haunts the novel, these other characters are resonant symbols of modernity, of the class and racial disorder that defines the novel's present. Given the realities of print publication, including page limits, it's understandable that those earlier character indices left so much out, but our nearly 2500 Unnamed characters help us re-present the racial and socio-economic demographics of Yoknapatawpha more accurately, and in particular make its Negro population much more visible. The 27 data fields we use to analyze each Character contain a number of interpretive assumptions that need to be made explicit. I've already discussed the Race field, but still need to acknowledge that it is our practice to assume that when a character's race is not made explicit by a narrator or clearly implied by the narrative context, that character is "White." Our policy here follows what we take to be Faulkner's own practice throughout the fictions. The situation with Ethnicity - another of those 27 - is the same: Faulkner's fiction calls attention to someone's ethnicity ('Jewish,' say, or 'Chinese') only when it's not the 'Scotch', 'Scotch-Irish' or 'Anglo-Saxon' norm for the white population of his county; unless the text makes an ethnicity explicit, we leave the field blank. We decided, however, that like Name, Gender, Rank, Class, Vitality and several other fields, in Faulkner's imagination every character has a race, and so in DY "Race" is a required field, though the field's menu also includes "Indeterminable," a category which we deploy in a few cases besides Joe Christmas. Rank allows us to register how important a Character's role is in a particular text. "Major," "Secondary" and "Minor" are probably self-explanatory - though again it's important to note that each Character entry is text-specific, so Colonel John Sartoris for example is Major in The Unvanquished, Secondary in "Ambuscade," and Minor in "The Sound and the Fury. It's equally important to acknowledge that these determinations are interpretive acts that can be second-guessed, and can be defended only on the basis of their interpretive utility. Rank includes a fourth option: in "Barn Burning" Colonel Sartoris is "Peripheral" - that is, a character who is referred to but never appears in a text. Unlike some of the published guides to Faulkner's characters, we don't include as "Characters" people like Cincinnatus or characters from other texts like Emma Bovary; in DY people who are mentioned but could never appear in Faulkner's world are included as Keywords, which we'll talk about below, under Events. DY's Vitality field includes a pair of categories that are definitely not self-explanatory. We decided to include "Dead-ghost" and "Alive-ghost" among the other options (Alive, Dead, Dies, Born, Born-and-Dies) as a way to capture one of the most distinctive characteristics of the world Faulkner created: the role played by what or who is 'not-there.' This of course includes "the past [that] is never dead," but also characters who are gone yet continue to haunt the present. Here again John Sartoris - and, interestingly, his namesake Johnny Sartoris - are cases in point. Caddy Compson also belongs in this cohort: the first two of these are dead before Flags in the Dust begins, and Caddy, though still alive, has disappeared from her brothers' lives before any of their sections begin in The Sound and the Fury, but all three of them are obsessively 'there' in the minds of other characters, absent and present at the same time. There aren't many of these characters, and I can understand that the categories themselves might seem arbitrary or whimsical, but this is another example of our attempt to keep our data as close to the fictions as possible. In our scheme Class in Faulkner's world is inextricably linked to Race. White Characters can belong to any of 5 categories: Upper, Middle, Lower, Yeoman and Poor White. In our judgment Faulkner's concept of the Upper class is essentially restricted to the members of the Yoknapatawpha families that owned property and slaves before the Civil War. The way we defined this for ourselves was: is a Character someone Virginia Sartoris Du Pre would invite to sit at her dinner table? They can be poor or even politically powerless, like Miss Emily Grierson, but their class status is not dependent on present-day wealth or power. Characters born outside this cohort can be rich or hold important offices but are Middle class at best, and (again in our judgment) in Faulkner's world the idea of the 'middle class' is considerably smaller than in most Americans' minds. The majority of the white characters we identify as Lower class. Like Faulkner's idea of a gentry, the concept of Yeomanry is also imported from England; Faulkner himself does not use the term, but the critic Cleanth Brooks is right to use it to characterize families like the MacCallums or even, in at least two short stories, the moneyless Griers: families who embody the best virtues of the South's traditional culture, including a willingness to fight for their values - an association with military service that actually links them to the original 14th century British definition of 'yeomanry.' Although class status in Faulkner's world often seems fixed by birth, some of his major characters clearly move across class lines, so our fields include a way to acknowledge when a character changes class within a text. But this possibility, of movement between classes, explains why we created separate Class categories for Indians and Negroes. If Faulkner's white South is quasi-aristocratic, the native American society he depicts is literally an aristocracy and so in our minds requires a different set of choices: Chief, Tribal Leader (a member of the chief's family), and Tribal Member. And given the Jim Crow social order depicted by Faulkner it strikes us as simply inappropriate to imply the possibility of socio-economic movement for black characters. Again, it isn't whether we think African Americans - in the South or anywhere - can't change classes, but whether Faulkner's fictions ever depict or even conceive such a possibility. In the data are one Upper and one Lower class black characters: both appear in "That Evening Sun" in the fairy tale that the black woman Nancy creates out of her imaginatively frantic desire to escape the real circumstances of her life (and here I can mention another Character field, the awkwardly named Ontological Status field, which includes "Character created by another Character" along with "Historical" and "Literary"). Four black characters are identified as Middle class. Otherwise we label all the Negro characters as either Enslaved or Free Black; for Negro characters the only times in which we check the "Character changes class in this text" box is when a fiction depicts someone Enslaved at the beginning and Free by the end as a result of emancipation or self-emancipation. Let me end this section with a much less controversial decision on our part. It seemed worthwhile to include Occupation among our Character fields. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics offered a ready-made set of categories in its index, so we relied on the nine occupational areas into which that agency sorts out the ways people make money - but it was immediately apparent to us that, at least as far as Faulkner's world was concerned, they had left out a crucial one: Crime. So we added that, and then, as a gesture toward the complexity of that world, also added Other. Less controversial, however, does not mean purely objective. Take the occupation of "blacksmith" - should this go under 'Sales and Service,' or 'Production,' or - as we ultimately decided - 'Transportation'? And while we believe that as long as we are consistent throughout the database about such editorial choices, you will find them useful, given the fact that 30 scholars entered Character data over almost a decade, we know consistency - like objectivity or thoroughness - remains a goal that is still imperfectly achieved. EventsIn the third database that provides information to the map displays are the 8400 Events into which we divide 'what happens' in the fictions. DY's instruction manual for creating these entries defines an "Event" as an episode that takes place at 1 Location during 1 unbroken length of time using 1 narrative technique - that is, we create a new Event each time the setting or time frame or narrative technique changes. For example, the different Narrative Status options are: "Narrated" (by a first- or third-person narrator), "Told" (by a character in the text), "Remembered" (by a character), "Hypothesized" (by a character or characters), and "Narrated+Consciousness" (when a passage combines narration with the stream-of-consciousness technique that Faulkner learned from James Joyce). Since narrative discontinuity, temporal disruption and perspectival multiplicity are hallmarks of Faulkner's experimental style, the lines between "Events" are not bright or impermeable. Think, for example, of the parts of the story of Thomas Sutpen in Absalom! that are 'told by Quentin to Shreve, as Quentin was told by his father Mr. Compson what he was told by his father, General Compson'! As always, however, our goal is interpretive utility: to re-present the stories in ways that can be displayed graphically, allowing users to see, for instance, how frequently a particular text moves backwards as well as forwards in time. Every Event is therefore assigned a date, though often this data point - even more often than the points in space that Locations occupy - requires an act of editorial interpretation. Faulkner's texts typically allow us to be reasonably certain about the temporal relationship between events (this, then that), but chronological markers are often broad or vague ("Spring," say, or "a year later," and so on). Scholars have argued for decades about which decade the main events of The Hamlet take place in, and if it's definite that As I Lay Dying takes place in "July," there's no way to know for sure exactly what year Faulkner had in mind. In many cases we simply provide a date range (yyyy-01-01 - yyyy-12-31, for example, is how we indicate "we think this happened sometime in yyyy"). In other cases we did not feel we could not be even that specific; on the chronological timeline you will occasionally see an Event plotted in this fashion -  - which is how we indicate an especially "Indeterminate Date Range." This instance is from "A Rose for Emily": the Event when "old lady Wyatt," Emily's aunt, went "completely crazy at last" (123). And in the more problematic cases our Note on the Text includes a section on "Dating the Story" in which we go into some detail about our reasons for deciding, for example, that most of The Hamlet takes place in the late 1890s. But almost all our dates are offered with the proviso that like so much else in Faulkner's world, the chronology of Yoknapatawpha is ambiguous, and we don't claim our decisions are the only possible ones. The textual bases for DY are the paperback editions of the 'Corrected Texts' prepared by Noel Polk that Vintage International has brought out for 21st century readers - that "(123)" in the previous paragraph for example references "A Rose for Emily" in the 1995 Vintage edition of Collected Stories of William Faulkner - but each Event is also identified by its First 8-10 words and by a Summary of what happens in it. Understandably, when we began sharing our plans for DY with the larger community of Faulkner scholars there was considerable concern that it might provide students in particular with an alternative to reading Faulkner. Our Event Summaries, however, are designed to give readers of Faulkner enough information to recognize an episode, but like DY as a whole, our intention is to enhance their reading experience, not to replace it. The entry for each Event also includes one or more Keywords. These allow you to use the project's Search Events function to search the Yoknapatawpha fictions for recurring themes, motifs, techniques and so on, using a set of tags supplied by the editors of each text. Keywords are explained in more detail at the Search Events page, but here are some examples of what you can search for and, theoretically at least, find every instance of in the canon; I'll list them according to the 3-part structure we evolved for our Keywords but you can search each of them as a single term: Environments>Time of Day>Twilight; Actions>Economic>Shopping; Cultural Issues>History>Indian Removal; Themes & Motifs>Recurring Tropes>Belatedness; Relationships>Familial>Parents-children; Aesthetics>Genre Conventions>Gothic. Keywords are still (as of June 2021) a work in progress, but we are more than halfway toward our goal to have every Event in every Yoknapatawpha fiction analyzed and keyworded by at least two editors. Instead of a ConclusionThe DY team discussed and often debated these concepts in person, in online meetings and in an untold number of emails, throughout the first years of the project. At one point or another we all became frustrated as the complexities and nuances of the world Faulkner created bumped up against the limits of what we felt we could achieve in virtual reality. In the end, because one thing we could agree on completely was that consistency was essential, everyone was willing with varying degrees of misgiving and consent to follow the same instructions for pulling that world through our data entry forms into the Location, Character and Event databases. Faulkner created his world almost entirely by himself, but DY is a thoroughly collaborative effort. It's only fair to the rest of the collaborators, however, to say that the ultimate responsibility for the decisions we made about how to re-present Yoknapatawpha, for what we did and didn't do, belongs to me. One of the consolations you have when you work on Faulkner is the high regard in which he himself always held 'failure.' — Stephen Railton Citing this source: |

Legend

| Map Features | |

|

A path through the forest surrounding the settlement that became Jefferson. This image also shows how we fade features that lie outside the scope of the text being mapped. |

|

Roads. Except for the roads in the town of Jefferson after 1920 or so, all the roads in Yoknapatawpha are unpaved - though gradually improved with gravel and better grading over time. |

|

Railroad. The one that Colonel Sartoris built after the Civil War. |

|

Left: Bridge. Not all the streams in Yoknapatawha are bridged; the image at right shows fords across two roads. |

|

Our maps display natural features in three colors. Here you can see trees (green), a hill (brown) and a stream (blue). |

|

Left: water features include Yoknapatawpha's two rivers, its creeks (or "branches"), springs and "sloughs" (one slough is shown here, alongside the county's northern river). Right: a swamp. |

|

Cultivated fields. The original forests were cut down to create them; we include them in the category of "man-made locations." |

| Locations | |

|

Cabin. |

|

Cemetery. |

|

Church. |

|

Event. We use this icon to identify locations that can't be represented by the other icons. |

|

Farm. |

|

House. |

|

Mansion. Sometimes this also represents an entire plantation as well as the "big house" there. |

|

Office or store. |

|

Other structure. This category includes Jefferson's water tower, or a lumber mill, a cotton house, a kitchen, a hunting camp and so on. |

|

Public building. This includes the courthouse at the center of the county and town, a school, a post office, the jail and so on. |

|

Statue or monument. |

|

A Yoknapatawpha Location that appears on an inset map. |

|

Any out of Yoknapatawpha Location, whether on an inset map or the REGION, NATION or WORLD maps. |

| Characters | |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as Asian. |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as Indian. |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as Negro. |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as White. |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as biracial: Negro and White. |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as biracial: Indian and White. |

|

The male and female icons for individual characters identified as biracial: Negro and Indian. |

|

The male and female icons for a character whose racial identity cannot be determined. We use this very sparingly. In Faulkner's world race is a very determinant category, although he typically specifies race only when someone is 'not white' - Indian, Negro, mulatto, quadroon, Japanese and so on. Nearly every character whose race is not made explicit is unquestionably imagined as white. But Joe Christmas falls between these categories, and there are a few other instances when we didn't feel comfortable assigning a race. |

|

The icon for the very few characters who are identified as multi-racial: Indian, White and Black. |

|

When two or more unnamed characters appear together, we use group icons to represent them. At left: the icon for a group identified as all-male (and Asian). This and the next 4 icons indicate the five categories of group icons you'll see. In this all-male category and the next two (all-female and both genders), each of the four races in the fictions have their own icons. |

|

The icon for groups that are identified as all-female. |

|

The icon for groups that are identified as containing both men and women or boys and girls. |

|

The icon for groups that are identified as mixed-race but single-gender. |

|

The icon for groups that are identified as mixed-race and dual-gendered. |

| Events | |

|

The vertical line that crosses the timeline below the map indicates the date on which a story begins narratively - that is, the chronological date of its first event. It is always specific to the text being mapped. Here, for example, it indicates that Flags in the Dust - Faulkner's first Yoknapatawpha fiction - opens in 1919, shortly after the end of World War I. |

|

When you animate a text, events will display in red - as "splashes" on the map and wider or thinner lines on the timeline - when they first appear. |

|

When the next event appears on the map and timeline, the previous one turns purple and remains visible to indicate where the story has been in space and time. |

|

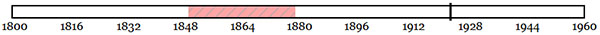

Most of the dates in DY's Event database are approximate, but when the possible date range is particularly large - more than half a decade - we use this hatching to indicate the uncertainty. |

- Log in to post comments

Comments

sfr

Tue, 2021-05-18 09:56

Permalink

Entered 17 May 2021.

Entered 17 May 2021.