Manuscripts Etc.

| CLOSE WINDOW |

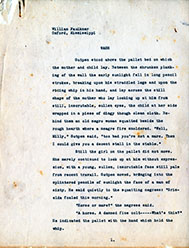

Special Collections and Archives, Southeast Missouri State University (http://www.semo.edu/cfs/). Click on any of these images to enlarge and see a transcription of it. “Wash” |

The Brodsky Collection contains two handwritten manuscripts and the typescript for "Wash." One of the stories these materials tell is how Faulkner began this short story at least four different times and three different ways. In the earliest extant manuscript (above left) he shifts focus almost immediately from Wash to Sutpen and the South's defeat. That beginning is cancelled after its third paragraph, and a new beginning started, one which keeps the focus on Wash and locates him as a poor white man among the slaves on Sutpen's plantation. The first page of the second manuscript (above center), clearly written later, starts with a revised version of this new beginning, though in this case only a paragraph was written before Faulkner decided to start somewhere else. At the top of this page you can see that he crossed out the title and wrote the number "2" over the "1" that was originally there. These details suggest that after writing out this paragraph Faulkner decided on yet another way to begin, and that this second manuscript was given a new page "1." That page is missing, but from the first uncancelled words on this page – "Which was a lie, as most of those" – it seems likely that if we could read it, it would contain a version of the way Faulkner ultimately chose to begin the story, by anticipating its final day and Sutpen's arrival at the fishing camp after the birth of his daughter. "Which was a lie" corresponds to the passage "This was a lie, as most of them . . . " in the published story's tenth paragraph. As you can see for yourself, the typescript of the story (above right) which Faulkner made before submitting the story for publication begins that way. (The only differences between the passage in the typescript and the published story are: "negro" and "negress" are capitalized, the spelling of "meagre" is Americanized, a new paragraph break introduced, and Faulkner's string of hyphens replaced with a conventional ellipsis. These changes were probably all made by the editors at Harper's Magazine.) Of course, Faulkner would "begin" Wash's story yet again, and give it yet a new emphasis, when he chose to interpolate it into Absalom, Absalom!, where the events of the short story are part of the narrative in Chapter VII. Other stories told by the manuscript of "Wash" emphasize reversals as Faulkner rearranges the beginning of page 5 (below) in order to (1) amplify Wash's new-found confidence in addressing arrogant Sutpen, the fifty-year-old war hero who has been giving inappropriate gifts to Wash's fifteen-year-old granddaughter, Milly, and (2) to throw into relief the perspective of poor whites and blacks vis-à-vis Milly's pregnancy two years later. Faulkner reintroduces the three deletions from the top of the page following the longer passage that begins "Now Wash's gaze no longer questioned." The result highlights Wash's inverted demeanor as he implicitly admonishes Sutpen to take care of Milly. Next we see how the first reintroduced line highlights Sutpen's anxiety as he averts his eyes from the poor white's face. The rearrangement and revisions of the third deletion indicate a time lapse of two years that includes the pregnancy of seventeen-year-old Milly and how poor whites and blacks interpret it. Faulkner writes three versions of "There were some, negroes, other poor whites" in the page's last block of text, and he lines through the first two as inadequately conveying the shared understanding of blacks and poor whites. Ultimately, Faulkner settles on a third version to indicate their belief that Wash prostituted his daughter to get Sutpen under his thumb. Notice how this version moves forward by fits and starts with an insertion from the margin and more deleted phrasing.

Yet another story told by the manuscript of "Wash" is evident in the editorial addition and subtraction on the top half of page 6 (below). The sentence in the margin emphasizes not only Wash's venerable status as a grandfather but, by extension, his identification with Sutpen that modifies Wash's understanding of the war hero. Two deletions, "thinking" replaced by "seeing" and "cried" replaced by "drawn breath," likely occur because Faulkner uses the deleted words later in the same sentences so he seeks to avoid unnecessary repetition. Sometimes a deletion does not lead to a better phrase as is evident in "I reckon I had, he said," which Faulkner deletes at the beginning of the last block of text only to reinsert it above the lined out sentence. At other times, a word is simply illegible as in the declaration that precedes "I reckon I had, he said." Here, the midwife says, "You [illegible] gawn tell him efn you going to." The illegible word appears to only have four letters, but The Comprehensive Guide to the Brodsky Collection transcribes it as "better," which matches what the midwife utters in the 1940 published version of "Wash.

The 12-page "working draft" and the 8-page "revised complete holograph" have been completely transcribed; see Faulkner: A Comprehensive Guide to the Brodsky Collection, Volume 5: Manuscripts and Documents (University Press of Mississippi, 1988), pp. 114-137. For more, see "The Textual Development of William Faulkner's 'Wash': An Examination of Manuscripts in the Brodsky Collection," by Louis Daniel Brodsky, Studies in Bibliography 37 (1984), pp. 248-81. Citing this source:

|