McCaslin Genealogies

|

CLOSE WINDOW |

Go Down, Moses: McCaslin Genealogies

|

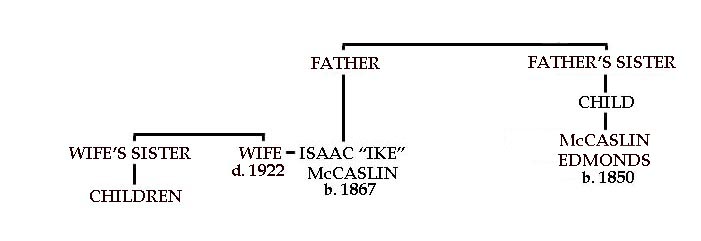

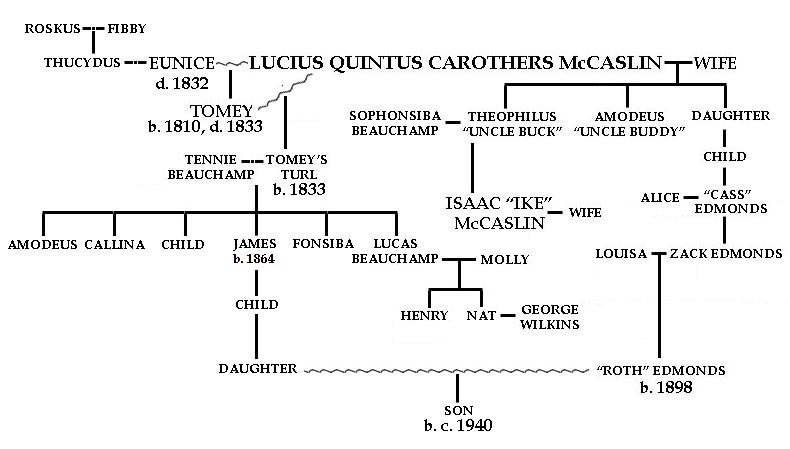

Go Down, Moses begins with a 3 paragraph introduction, set off from the rest of the story "Was" by being written as one sentence in Faulkner's high style. Its first four words — "Isaac McCaslin, 'Uncle Ike'" — apparently identify the novel's central character (after this opening, Ike is not mentioned again until the novel's second chapter). Although it notes that the title to the McCaslin land was acquired from the "Indians," it makes no mention of the McCaslin (Ike's grandfather) who acquired it. It mentions that "some of the descendants" of the slaves of Ike's unnamed "father" are also named McCaslin, but there is no suggestion that these people are members of the McCaslin family, however extended (everywhere else in the novel the descendants of McCaslin slaves are all named Beauchamp). The chart below represents the McCaslin family as it is outlined in this introductory:

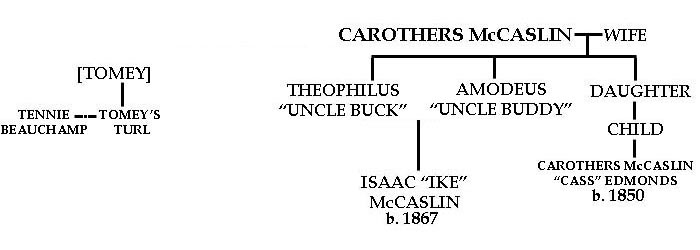

After finishing "Was" readers have a larger, though not necessarily a clearer understanding of the family. We learn that "Cass" Edmonds was named for his great-grandfather, Carothers McCaslin, the original owner of the plantation, and that this man had twin sons, either one of whom could have been Ike's father. The name of the slave who runs away from the McCaslin plantation to visit Tennie on the Beauchamp plantation — "Tomey's Turl" — implies a mother named "Tomey," and the fact that Hubert Beauchamp thinks of Tomey's Turl as "that damn white half-McCaslin" implies a white father named McCaslin, presumably one of the men on the chart below, which attempts to represent the way we see the family by the end of "Was":

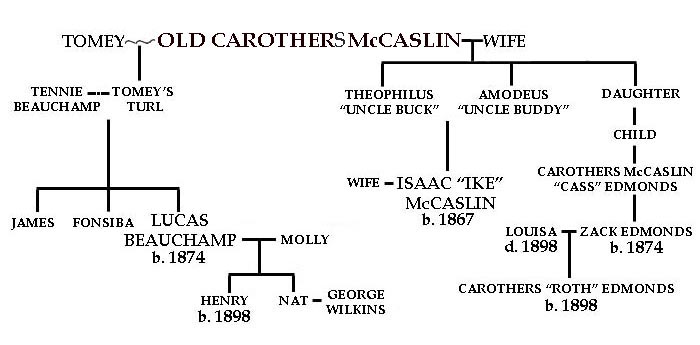

In "The Fire and the Hearth" Ike's father is still not established, but Tomey's Turl's is: he is Ike's McCaslin grandfather, referred to in this story as "Old Carothers." The story's central character is Lucas Beauchamp, who is described and who repeatedly refers to himself as a direct male "descendant" of this founding father, "even though in the world's eye he descended not from McCaslins but from McCaslin slaves" — that is to say, to Yoknapatawpha Lucas is 'black,' although his lineage is common knowledge. In the course of this long story we also hear about the following members of the McCaslin family, "black" and "white":

Little more about the McCaslins is learned in the novel's next two chapters. In "Pantaloon in Black" readers are told that Rider rents his cabin from Carothers (Roth) Edmonds, "the local white land owner," and that he built an undying fire on his hearth in imitation of "Uncle Lucas Beauchamp, Edmonds' oldest tenant" — these are the story's only mentions of the McCaslins. In "The Old People," readers meet "Tennie's Jim," the son of Tomey's Turl and Tennie Beauchamp who is called "James" in "The Fire and the Hearth," but his place on the McCaslin family tree is not specifically noted.

The final two chapters — "Delta Autumn" and "Go Down, Moses" — bring the family story almost up to the date of the novel's 1942 publication. In "Delta Autumn" Ike, now over 70 and on his annual November hunting trip, meets the woman who has been having an affair with Roth Edmonds, Ike's cousin Cass's grandson and the owner of the McCaslin property. Much to Ike's surprise and dismay, this unnamed young woman turns out to be the grand-daughter of Lucas Beauchamp's brother James ("Tennie's Jim"), whom Ike had traced into Tennessee and then lost in "The Bear." This means she is a "black" McCaslin, and also means that her relationship with Roth is technically both incest and miscegenation, like Old Carothers McCaslin's sexual relationships with Tomey one hundred years earlier. It also means that the infant son she carries into Ike's tent is Ike's youngest living relative. She wants Roth (who does not know about her McCaslin roots) to marry her. Ike tells her that "maybe" in a thousand more years an interracial marriage will be possible. Until then, he passes on the answer Roth gave him (along with money, perhaps as much as the $1000 Old Carothers left Tomey's Turl in his will). The answer, Roth says, is No. Ike also gives her son one of his few possessions: the silver-chased hunting horn General Compson left him in his will. As of this story, the McCaslin family tree looks like this:

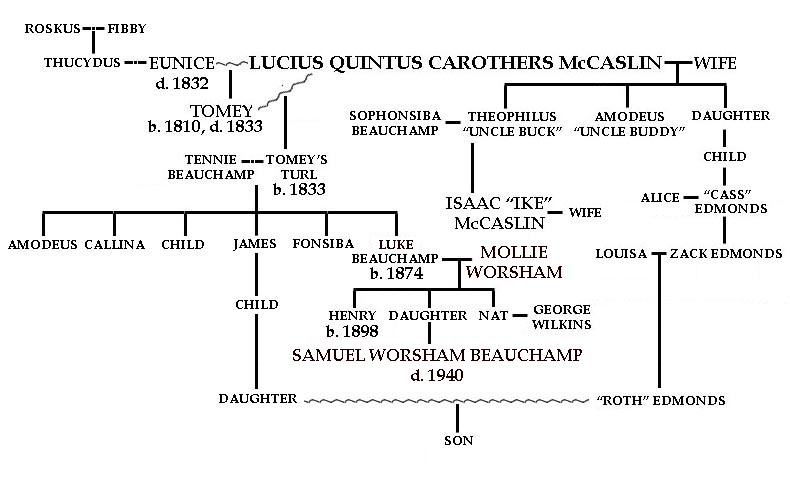

The final story must be set in 1940, a census year. It features Mollie Beauchamp, Luke's wife (as Molly and Lucas are now named). In it we learn that Mollie's maiden name was "Worsham," the name of the white family who owned her parents before the Civil War, and that she and Luke had at least one other child besides Henry and Nat: a daughter whose son is named Samuel Worsham Beauchamp. Like the young woman in "Delta Autumn," Samuel has been living in the North. The story opens on the day he is executed in Illinois for killing a Chicago policeman, and ends as the funeral procession arranged by Gavin Stevens so that Mollie can bring the body home goes out of sight on its journey to the McCaslin estate. Roth Edmonds, whom Mollie blames for her grandson's fate, is still the owner of the plantation. Since it seems unlikely that he will marry, and since his illegitimate son disappears at the end of "Delta Autumn," the McCaslin genealogy looks like this at the end of the line:

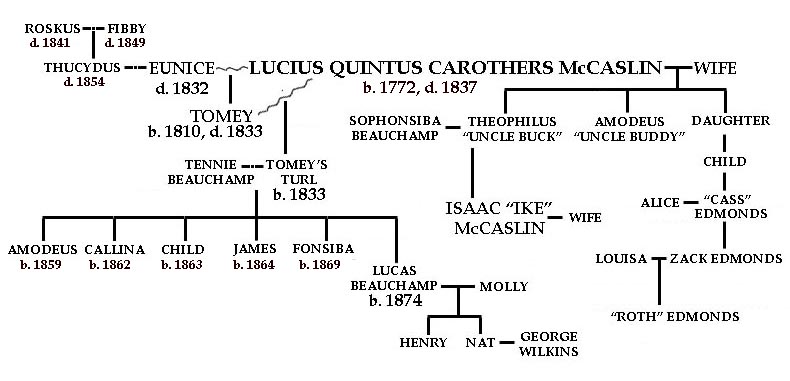

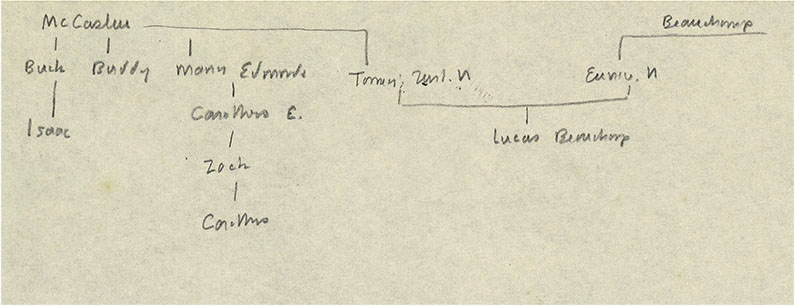

It's interesting to compare the McCaslin story as Faulkner wound up narrating it with the genealogy he made for himself when he began revising the various short stories that make up the novel into the larger Go Down, Moses text. According to Joseph Blotner's biography, it was "probably" in the spring of 1941 that "Faulkner sketched out in pencil a genealogical chart" (as Blotner notes, the "N" next to Tomey's Turl and Eunice must mean "Negro"). As you can see, there are major differences between this chart and the family history as the novel tells it. Here for example [Old Carothers] McCaslin's daughter is given a first name – Mary - and identified as married to Edmonds and as Cass's mother; in the novel "Uncle Buck's and Uncle Buddy's sister" is referred to as Cass' "grandmother," meaning that it is her child who marries an Edmonds. More significantly, Faulkner's chart doesn't identify the mother of "Tomey's Turl" at all, much less indicate that he is both the son and the grandson of the original McCaslin:

SOURCES: Blotner, Faulkner: A Biography; William Faulkner Foundation Collection, 1918-1959, Accession #6074 to 6074-d, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia Library: Chart 1 p. (1 R, 0 V) on 1 l. Genealogical chart in pencil showing the McCaslin-Edmonds-Beauchamp connections. Citing this source:

|